Merger Arbitrage

Overview

Dive into the world of merger arbitrage and learn about the strategy’s history, characteristics, and uses in portfolio construction.

Key Topics

Merger Arbitrage, Risk Arbitrage, Mergers & Acquisitions, Alternatives

Table of Contents

What is Merger Arbitrage?

Merger arbitrage, also known as risk arbitrage, is an investment strategy that seeks to profit from the price discrepancies that often occur in the stock market during corporate mergers and acquisitions (M&A). This strategy is typically implemented by professional investment managers, including hedge funds and specialized arbitrage funds, as part of a broader portfolio management process. The core premise of merger arbitrage is that the stock price of the target company in an M&A deal will typically trade at a discount to the announced acquisition price, providing an opportunity for arbitrageurs to profit from this spread.

Merger arbitrage strategies primarily involve taking long positions in the stock of the target company and, in the case of stock-for-stock deals, short positions in the stock of the acquiring company. The arbitrageur’s goal is to capture the spread between the current market price of the target company’s stock and the expected value of that stock when the deal closes. This spread exists due to various factors, including the time value of money, the risk that the deal may not be completed, and potential regulatory hurdles.

Similar to other arbitrage strategies, merger arbitrage typically involves relatively low-risk returns, as the outcome of the investment is primarily dependent on the successful completion of the announced deal rather than broader market movements. However, the strategy is not without risks, as deals can fall through due to various factors such as regulatory issues, financing problems, or changes in market conditions.

The specific assets that a merger arbitrageur may trade typically include:

- Common stocks of target and acquiring companies

- Options on these stocks

- Corporate bonds (in the case of leveraged buyouts)

- Convertible securities

To enhance diversification, merger arbitrage managers often engage in multiple deals simultaneously, spreading their risk across various sectors and geographies. This approach helps to mitigate the potential impact of any single deal failing to close.

Merger arbitrage strategies are predominantly systematic in nature, relying on quantitative models to assess the probability of deal completion and the expected returns.

These models typically consider factors such as historical deal completion rates, regulatory environment, financing conditions, deal terms and structure, and market sentiment.

Types of Merger Arbitrage Strategies

There are several ways to implement a merger arbitrage strategy, each with its own risk-reward profile:

- Cash Deals: In a cash acquisition, the arbitrageur simply buys the target company’s stock and waits for the deal to close. The profit is the difference between the purchase price and the acquisition price, minus any transaction costs.

- Stock-for-Stock Deals: These involve shorting the acquiring company’s stock while going long on the target company’s stock. The arbitrageur aims to profit from the convergence of the exchange ratio as the deal approaches completion.

- Mixed Consideration Deals: These deals involve a combination of cash and stock. The arbitrageur must carefully balance their positions based on the specific terms of the deal due to the complexities involved.

- Stub Trades: This strategy involves buying or shorting the “stub” of a company, which is the remaining business after a spin-off or partial acquisition.

- Distressed Merger Arbitrage: This involves investing in the securities of distressed companies that are potential takeover targets, often in bankruptcy situations.

Factors Influencing Merger Arbitrage Returns

Several factors can impact the returns of merger arbitrage strategies:

- Deal Spread: The wider the spread between the current market price and the acquisition price, the higher the potential return. However, wider spreads often indicate higher perceived risk of deal failure.

- Time to Completion: Longer deal timelines can increase the annualized returns but also expose the arbitrageur to more risk.

- Market Volatility: High market volatility can create larger spreads and more opportunities, but it can also increase the risk of deals falling through.

- Regulatory Environment: Stricter antitrust regulations or other regulatory hurdles can impact deal completion rates and arbitrage returns.

- Competing Bids: The emergence of competing bids can increase the potential upside but also adds complexity to the arbitrage situation.

Merger arbitrage remains a popular strategy among sophisticated investors due to its potential for consistent, low-correlation returns. However, successful implementation requires deep expertise in deal analysis, risk management, and sometimes complex financial instruments. As with any investment strategy, thorough due diligence and a clear understanding of the risks involved are crucial for those considering merger arbitrage as part of their investment approach.

History of Merger Arbitrage

Merger arbitrage, also known as risk arbitrage, is a strategy that has evolved significantly over time, playing a crucial role in the landscape of financial markets and corporate finance. The concept of profiting from corporate mergers and acquisitions (M&A) has its roots in the early days of modern finance, but its systematic application as an investment strategy has developed substantially over the past century.

The origins of merger arbitrage can be traced back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries when the United States experienced a wave of corporate consolidations. During this period, astute investors began to recognize opportunities to profit from price discrepancies between the announced deal terms and the trading prices of involved companies.

One of the earliest and most notable practitioners of merger arbitrage was Benjamin Graham, often referred to as the “father of value investing”. In his seminal work, “Security Analysis,” co-authored with David Dodd in 1934, Graham discussed the concept of arbitrage operations, laying the groundwork for what would later become known as merger arbitrage.

The development of merger arbitrage as a systematic investment strategy can be broadly divided into several phases:

- Early Recognition (1920s-1950s): During this period, sophisticated investors began to recognize and exploit opportunities in corporate reorganizations and mergers. However, the strategy remained largely the domain of a select few due to limited information availability and high transaction costs.

- Professionalization (1960s-1970s): The 1960s saw the emergence of professional arbitrageurs who specialized in merger-related investments. Ivan Boesky, despite his later notoriety for insider trading, was one of the pioneers in developing merger arbitrage into a full-fledged investment strategy.

- Institutional Adoption (1980s-1990s): The merger boom of the 1980s, fueled by hostile takeovers and leveraged buyouts, led to increased interest in merger arbitrage from institutional investors. Hedge funds began to allocate significant capital to the strategy, recognizing its potential for generating uncorrelated returns.

- Quantitative Evolution (2000s-present): With advancements in computing power and data availability, merger arbitrage has increasingly incorporated quantitative techniques. Modern practitioners use sophisticated models to assess deal probabilities, regulatory risks, and optimal position sizing.

Several key figures and events have shaped the evolution of merger arbitrage:

- Gustave Levy: As a partner at Goldman Sachs in the 1940s, Levy was instrumental in developing the firm’s risk arbitrage department, one of the first of its kind on Wall Street.

- Martin Shubik: Shubik published “The Theory of Money and Financial Institutions” which included some of the earliest academic treatments of arbitrage in corporate control transactions.

- Michael Price: As the manager of Mutual Shares Fund, Price was known for his successful merger arbitrage strategies in the 1980s and 1990s, demonstrating the potential of the strategy in a mutual fund format.

The landscape of merger arbitrage has been significantly influenced by regulatory changes and market events. The Williams Act of 1968, which mandated disclosure of tender offers and other key information in M&A transactions, provided arbitrageurs with more reliable data on which to base their decisions.

The development of merger arbitrage as a risk premia strategy gained traction in the 1990s and 2000s. Researchers began to view merger arbitrage returns as compensation for bearing deal completion risk, rather than pure alpha. This perspective was reinforced by studies showing that merger arbitrage returns exhibited low correlation with traditional asset classes, making them attractive for portfolio diversification.

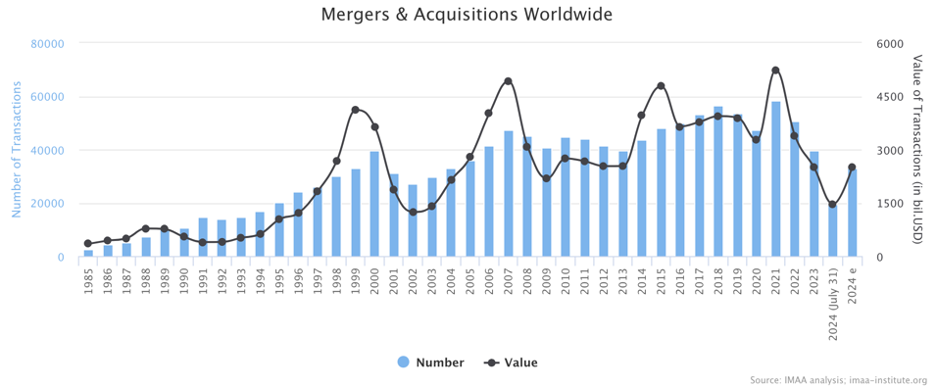

Number and Value of M&A Transactions Worldwide from 1985 to 2024

In modern portfolio management, merger arbitrage strategies have become an integral part of many alternative investment programs. They are often combined with other event-driven strategies to create more robust and diversified investment approaches.

The strategy has also evolved to include different variations, such as cash mergers arbitrage, stock-for-stock mergers arbitrage, mixed consideration deals arbitrage, and SPAC arbitrage (a more recent development).

As merger arbitrage continues to evolve, it remains a subject of ongoing research and innovation in the investment industry. The interplay between merger arbitrage and other factors, such as market sentiment and regulatory environments, continues to be an area of active investigation, promising further refinements in strategy design and implementation.

The future of merger arbitrage is likely to be shaped by advancements in technology, changes in global M&A activity, and evolving regulatory landscapes. As markets become more efficient and competition increases, practitioners will need to continue innovating to maintain the strategy’s effectiveness as a source of uncorrelated returns in diversified portfolios.

Theoretical Foundations of Merger Arbitrage

Merger arbitrage, also known as risk arbitrage, is an investment strategy that seeks to profit from the price discrepancy between a target company’s stock price and the acquisition price offered by the acquiring company. The persistence and profitability of merger arbitrage strategies have led researchers to develop theoretical frameworks to explain why these opportunities exist in markets and why they may continue to provide returns.

Why Merger Arbitrage Opportunities Exist

Merger arbitrage opportunities arise due to several factors that create inefficiencies in the market:

- Risk Premium: The spread between the target company’s stock price and the offer price represents a risk premium that compensates investors for the uncertainty of deal completion. Mitchell and Pulvino argue that merger arbitrage returns are compensation for bearing the risk of deal failure.

- Market Structure: Institutional factors, such as regulatory constraints and market segmentation, can create persistent arbitrage opportunities. For instance, certain investors may be prohibited from holding shares of companies involved in mergers, creating selling pressure and widening the spread.

- Information Asymmetry: The complexity of merger transactions and the potential for private information can lead to pricing inefficiencies. Baker and Savasoglu suggest that arbitrageurs with superior information processing skills can exploit these inefficiencies.

- Limited Capital: The amount of capital dedicated to merger arbitrage strategies is finite, which can lead to persistent opportunities, especially during periods of market stress when capital becomes scarce.

Academic Theories and Explanations

Several academic theories have been developed to explain the returns associated with merger arbitrage:

- Risk-Based Explanations: Researchers such as Jindra and Walkling, 2004 argue that merger arbitrage returns are compensation for systematic risk factors, including market risk and deal completion risk.

- Behavioral Finance Perspectives: Shleifer and Vishny, 1997 propose that limits to arbitrage, including funding constraints and noise trader risk, can explain the persistence of merger arbitrage opportunities.

- Option-Like Payoff Structure: Brown and Raymond, 1986 characterize merger arbitrage as essentially a put option written on the target company’s stock, with the strike price equal to the offer price.

- Returns During Market Downturns: Mitchell and Pulvino, 2001 find that merger arbitrage returns exhibit option-like features, providing positive returns in most market environments but suffering losses during severe market downturns.

Merger Arbitrage Across Different Deal Types

While the concept of merger arbitrage is universal, its manifestation and drivers can vary across different types of merger and acquisition transactions:

- Cash Deals: In cash transactions, the arbitrage spread is typically smaller and more straightforward to calculate making the primary risk deal completion.

- Stock Deals: Stock-for-stock transactions introduce additional complexity due to the fluctuating value of the acquisition currency. Branch and Yang, 2006 highlight that this complexity can lead to greater mispricing and potential arbitrage opportunities.

- Mixed Consideration Deals: Transactions involving a combination of cash and stock present unique challenges for arbitrageurs. Bhagat, Brickley, and Loewenstein, 1987 find that the market’s reaction to mixed consideration deals differs from pure cash or stock transactions.

- Hostile Takeovers: Hostile deals often present wider spreads due to the increased uncertainty of completion. Schwert, 2002 documents that hostile takeovers are associated with higher premiums and potentially greater arbitrage opportunities.

Risk Factors in Merger Arbitrage

Understanding the risk factors associated with merger arbitrage is crucial for investors considering this strategy:

- Deal Break Risk: The primary risk in merger arbitrage is the possibility of deal failure. Malmendier, Opp, and Saidi, 2012 find that failed deals can result in significant losses for arbitrageurs.

- Regulatory Risk: Antitrust concerns and regulatory approvals can significantly impact deal completion. L. Mitchell and Mulherin, 1996 highlight the importance of considering regulatory factors in assessing merger arbitrage opportunities.

- Financing Risk: In leveraged buyouts or deals with significant debt financing, the ability to secure funding can impact deal closure. Kaplan and Stein, 1993 discuss the role of financing conditions in merger transactions in the 1980s.

- Market Risk: While merger arbitrage is generally considered a market-neutral strategy, extreme market conditions can affect returns.

While no single theory fully explains the returns associated with this strategy, the combination of risk premia, market inefficiencies, and complex deal structures contribute to the ongoing presence of arbitrage opportunities in merger and acquisition transactions. As with any investment strategy, understanding these theoretical underpinnings is essential for investors and portfolio managers considering the inclusion of merger arbitrage in their investment approach.

Existing Merger Arbitrage Indices and Benchmarks

There are several indices and benchmarks that have been developed to track merger arbitrage strategy performance:

- IQ Merger Arbitrage Index: This index aims to track the performance of global companies for which there has been a public announcement of a takeover by an acquirer.

- S&P Merger Arbitrage Index: This index provides exposure to a global merger arbitrage strategy, including a short exposure to the global equity markets to hedge out market risk.

- S&P Long-Only Merger Arbitrage Index: This index provides exposure to up to forty names that are pending targets of a merger deal.

- HFRI ED Merger Arbitrage Index: This index, maintained by Hedge Fund Research, Inc., tracks the performance of merger arbitrage hedge funds.

- Credit Suisse Merger Arbitrage Liquid Index: This index seeks to gain broad exposure to the merger arbitrage strategy using a pre-defined quantitative methodology to invest in announced deals.

Additional Literature, Theoretical Evidence, and Implications for Portfolios

Merger arbitrage, also known as risk arbitrage, has been a subject of significant academic research and practical interest in the field of finance. This section reviews key academic papers, empirical evidence, and the implications of incorporating merger arbitrage strategies into investment portfolios.

Baker and Savasoglu, 2000 examine the risk and return characteristics of merger arbitrage. The authors find that merger arbitrage generates significant excess returns, which they attribute to the limited capital available for this strategy and the specialized skills required to implement it effectively.

Mitchell and Pulvino, 2001 provide a comprehensive analysis of merger arbitrage returns from 1963 to 1998. The authors find that merger arbitrage returns are positively correlated with market returns during severe market downturns, but uncorrelated with market returns in flat and appreciating markets. This nonlinear relationship suggests that merger arbitrage can potentially offer diversification benefits to traditional portfolios.

Hsieh and Walkling, 2004 explore the limits to arbitrage in merger situations. They find that arbitrageurs play a significant role in the market for corporate control, and their actions can influence both the probability of deal success and the returns to target shareholders.

Branch and Yang, 2006 investigate the profitability of merger arbitrage strategies across different market conditions. The authors find that merger arbitrage can generate consistent returns, but the strategy’s performance is sensitive to market-wide merger and acquisition activity.

Cao et al. 2011 investigate the application of machine learning techniques to merger arbitrage strategies. Their research suggests that machine learning models can potentially enhance the performance of traditional merger arbitrage approaches by better predicting deal outcomes and optimal position sizing.

Golubov, Petmezas, and Travlos, 2013 investigate the relationship between idiosyncratic risk and merger arbitrage returns. Their findings suggest that idiosyncratic risk is a significant driver of merger arbitrage returns, highlighting the importance of deal-specific factors in this strategy.

Van Tassel, 2016 analyzed the predictive power of option prices in forecasting the outcomes of mergers and acquisitions, finding that a dynamic asset pricing model incorporating target stock and option prices yields more accurate predictions than existing methods. This model particularly enhances forecasts in merger arbitrage, where deal success is associated with low volatility and a high Sharpe ratio, indicating a strong risk-adjusted return when deals are likely to succeed.

Performance History

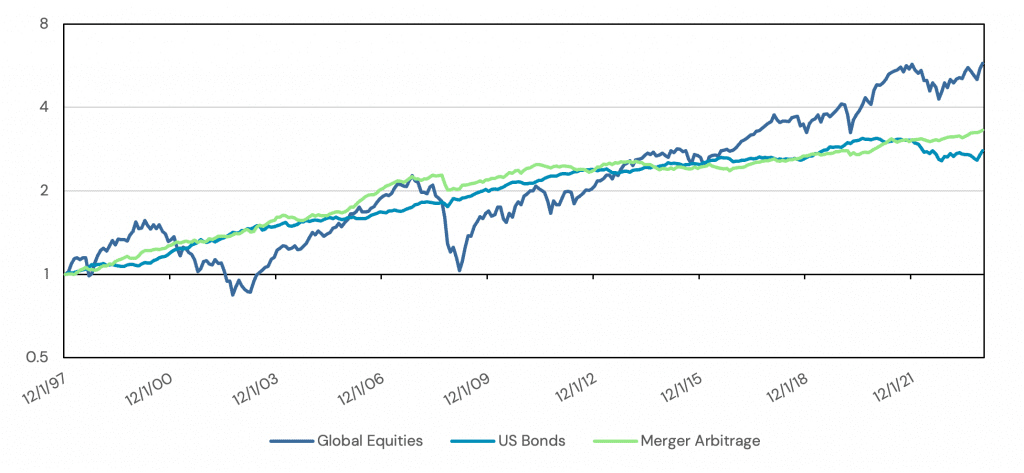

In this section, we show the historical performance of merger arbitrage,, using the Credit Suisse Merger Arbitrage Liquid Index, in relation to global equities, US Bonds, and a balanced 60/40 portfolio.

Historical Performance and Statistics

Source: Bloomberg, Credit Suisse, FRED, Philadelphia Fed. Performance is backtested and hypothetical. Performance data begins in 1997 and ends in 2023 due to data availability. Performance is gross of all costs (including, but not limited to, advisor fees, manager fees, taxes, and transaction costs) unless explicitly stated otherwise. Performance assumes the reinvestment of all distributions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. See Appendix A for index definitions.

Source: Bloomberg, Credit Suisse, FRED, Philadelphia Fed. Performance is backtested and hypothetical. Performance data begins in 1997 and ends in 2023 due to data availability. Performance is gross of all costs (including, but not limited to, advisor fees, manager fees, taxes, and transaction costs) unless explicitly stated otherwise. Performance assumes the reinvestment of all distributions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. See Appendix A for index definitions.

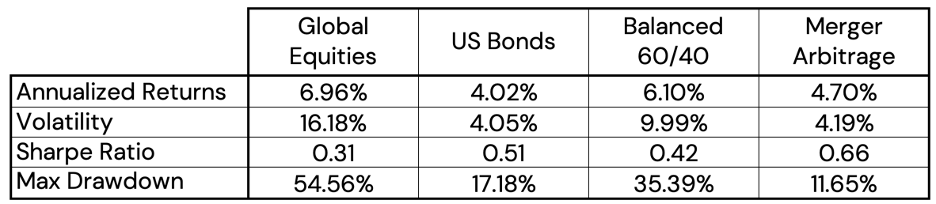

Performance During Equity Drawdowns (Greater than 20%)

Source: Bloomberg, Credit Suisse, FRED, Philadelphia Fed. Performance is backtested and hypothetical. Performance data begins in 1997 and ends in 2023 due to data availability. Performance is gross of all costs (including, but not limited to, advisor fees, manager fees, taxes, and transaction costs) unless explicitly stated otherwise. Performance assumes the reinvestment of all distributions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. See Appendix A for index definitions.

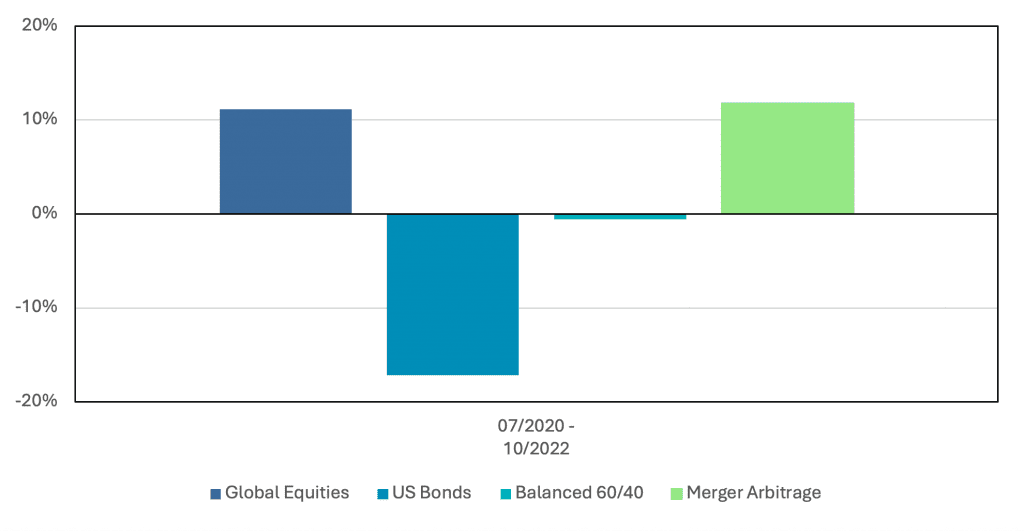

Performance During Fixed Income Drawdowns (Greater than 5%)

Source: Bloomberg, Credit Suisse, FRED, Philadelphia Fed. Performance is backtested and hypothetical. Performance data begins in 1997 and ends in 2023 due to data availability. Performance is gross of all costs (including, but not limited to, advisor fees, manager fees, taxes, and transaction costs) unless explicitly stated otherwise. Performance assumes the reinvestment of all distributions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. See Appendix A for index definitions.

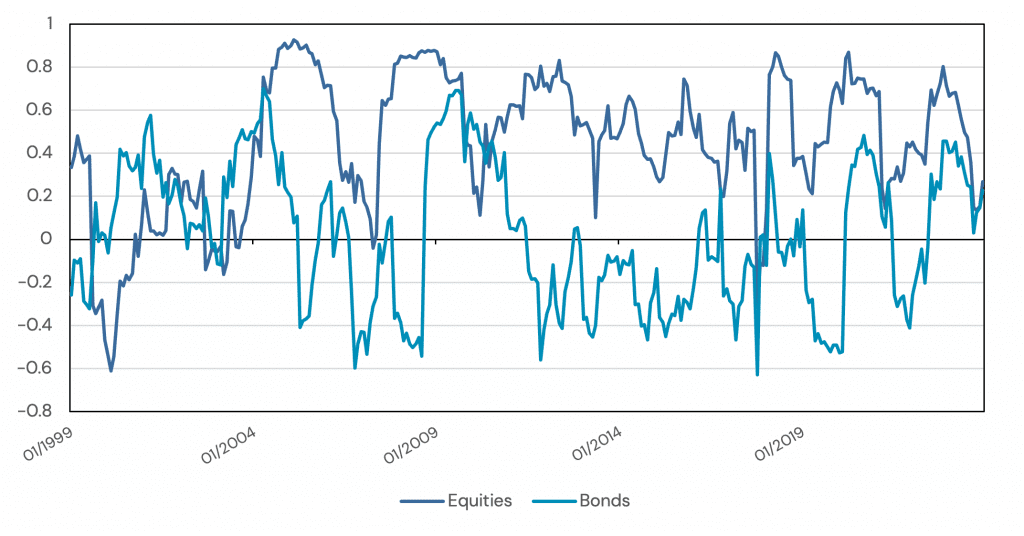

Rolling 12-Month Correlation to Stocks and Bonds

Source: Bloomberg, Credit Suisse, FRED, Philadelphia Fed. Performance is backtested and hypothetical. Performance data begins in 1997 and ends in 2023 due to data availability. Performance is gross of all costs (including, but not limited to, advisor fees, manager fees, taxes, and transaction costs) unless explicitly stated otherwise. Performance assumes the reinvestment of all distributions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. See Appendix A for index definitions.

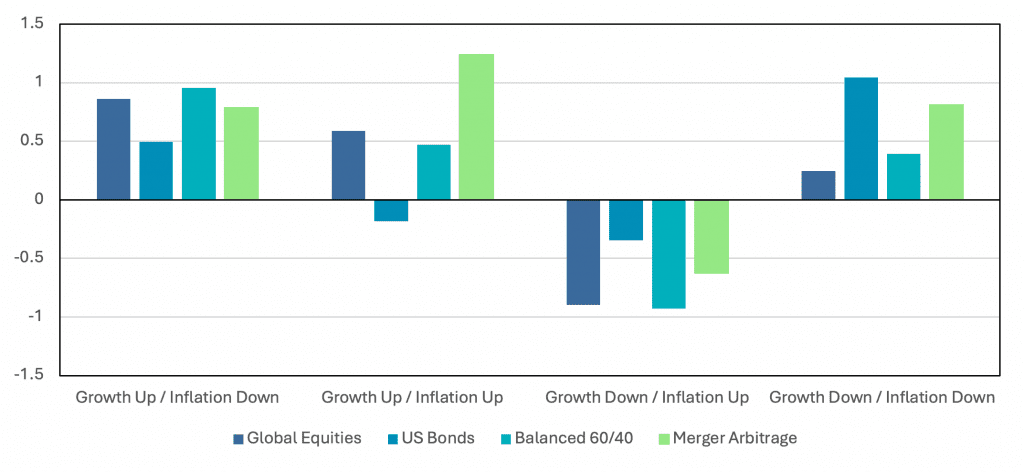

Sharpe Ratios During Macroeconomic Regimes

Source: Bloomberg, Credit Suisse, FRED, Philadelphia Fed. Performance is backtested and hypothetical. Performance data begins in 1997 and ends in 2023 due to data availability. Performance is gross of all costs (including, but not limited to, advisor fees, manager fees, taxes, and transaction costs) unless explicitly stated otherwise. Performance assumes the reinvestment of all distributions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. See Appendix A for index definitions.

Potential Applications to Return Stacking

There is a substantial body of historical evidence supporting the viability of merger arbitrage as a stand-alone investment strategy. The strategy’s empirical record of holding low correlations to both equity and fixed income markets supports its place as a potentially diversifying asset to traditional investment portfolios. On top of those foundational aspects, why might an investor choose to include merger arbitrage in a portfolio?

Below we show some examples of how one might contemplate use cases for merger arbitrage in an investment portfolio.

Return Stacking Merger Arbitrage for Growth

Investors with a long investment horizon can bear more risk in the hopes of achieving a higher growth rate. Traditionally, an investor in this scenario would hold a high allocation to stocks with little, if any, fixed income allocation.

Merger arbitrage offers an additional opportunity for growth-oriented investors. By stacking merger arbitrage strategies on top of core assets like equities and bonds, portfolios can potentially maintain their existing exposure to equities while accessing an additional return stream. Furthermore, the empirically low correlation between equities and merger arbitrage may provide increased diversification benefits to the overall portfolio.

Return Stacking Merger Arbitrage for Diversification

One of the most common investment portfolios is the 60/40 stock and bond portfolio. Investors have become accustomed to bonds being a reliable complement to equities, specifically in equity drawdowns. However, the low correlations between stocks and bonds that many investors depend on may not be supported by a broader historical perspective.

Commensurately, there are two reasons to consider adding a third leg to the stock/bond stool. The first consideration would be the potential improvement of a portfolio from adding an additional uncorrelated asset. The second would be the new asset’s sensitivity to economic regimes.

Appendix A: Index Definitions

Global Equities – The MSCI ACWI Total Return Index (Bloomberg ticker: MXWD Index). Performance is gross of all costs (including, but not limited to, advisor feed, manager fees, taxes, and transaction costs). Source: Bloomberg.

US Bonds – The Bloomberg US Aggregate Total Return Value Unhedged USD Index (Bloomberg ticker: LBUSTRUU Index). Performance is gross of all costs (including, but not limited to, advisor feed, manager fees, taxes, and transaction costs). Source Bloomberg.

Merger Arbitrage – The Credit Suisse Merger Arbitrage Liquid Index seeks to gain broad exposure to the Merger Arbitrage strategy by using a pre-defined quantitative methodology in order to invest in a liquid, diversified and broadly representative set of announced merger deals. The Merger Arbitrage Liquid Index is also a factor within the Credit Suisse Event Driven Liquid Index.

Balanced 60/40 – A monthly rebalanced portfolio consisting of a 60% allocation the MSCI ACWI Total Return Index and a 40% allocation to the Bloomberg US Aggregate Total Return Value Unhedged USD Index. Performance is gross of all costs (including, but not limited to, advisor feed, manager fees, taxes, and transaction costs). Source Bloomberg.

Appendix B: Regime Definitions

To assess the macroeconomic regimes, we adapt the methodology outlined by Ilmanen (2014). Growth and Inflation are each defined as a composite of two series, which are first normalized to z-scores by subtracting the historical mean and dividing by the historical volatility.

“Up” and “Down” regimes are defined as those times when measures are above or below their full sample median.

Growth:

- The Chicago Fed National Activity Index

- Realized Industrial Production minus prior year Industrial Production forecast from the Survey of Professional Forecasters.

Inflation:

- Year-over-year CPI change.

- Realized year-over-year CPI minus prior year NGDP forecast from the Survey of Professional Forecasters.